When I look back at my life, I see mostly brief intervals, not long passages. If my life were a YouTube video, it would be a series of 30-60 second “shorts.” Not that there isn’t enough substance for more. There has been considerable drama, tumult and joy. But the events have sped by in a fluid timeline, like a recording being fast-forwarded.

I wonder why. Is it because I never learned to rest in the moment, to savor the day I’m in? Instead of having my feet planted in place, I’ve been perched like a bird waiting to fly away.

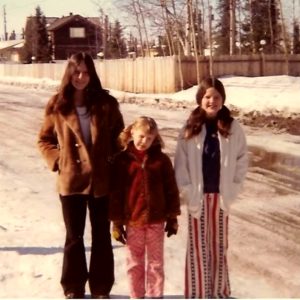

Or maybe it’s because throughout my childhood, things were in flux. We moved constantly. I got used to changing homes, schools and sometimes cities. I had a bunch of aunts, uncles and cousins, but they were mostly in the south while we were in Anchorage. I had one aunt and uncle in Anchorage, and they had two boys and a girl. My sisters and I were close to them for a few years, but then we moved (again), this time to a couple different places in California, then four months in Mississippi.

I learned family meant only the five of us. We seldom lived near our extended family. It was mostly just my parents and the three girls. And we weren’t supposed to talk about “the family business.”

Not long ago I was watching one of those insipid housewives’ shows when something struck me. One of the women said, “If you don’t have family, you don’t have anything.” The woman and her husband have been feuding with his sister for years. They cannot get along for a sustained time. She was telling her daughter that she needs to have a good relationship with her siblings, because there is nothing more important than family. They are Italian, and in their culture, you are ride or die with your “blood.”

I’ve heard the estranged sister say the same thing to her daughters, even though she fights constantly with her brother. The hypocrisy rankled me. It reminded me of my mother saying the same thing to my sisters and me. I grew up hearing her talk about how important family relationships were, even though my mother was constantly feuding with her siblings. Usually it was one of her three sisters, but sometimes it was a brother.

These weren’t just spats. They were heated arguments: screaming, name-calling, below the belt stuff from the past being brought up and the phone hung up so dramatically it dinged (back when there were real phones). Many were alcohol-fueled, but not all.

Sometimes with the sisters, it even got physical. Once there was a horrible physical fight between my mother and aunt. There was hair-pulling, shoving and slapping. My mother had just been released from the hospital, and in her weakened state she was losing the fight. She tried to call my dad and my aunt pulled the phone out of the wall. My three cousins, sisters and I were crying and screaming. I was around 8.

But most of the time, my mother’s family troubles were more about “shade” being thrown, as they say nowadays. She’d comment about one of her sisters, how she was “jealous” or “hung up on status” or “a mess.” And there were times I’d be around one of my aunts and overhear them say something similar about my mother. Not in front of me, but when they thought I was out of hearing range. Once I heard my aunt telling another sister someone that my mother’s twin sister was prettier. I thought it was mean and not true. I felt hurt for my mother.

My mother grew up with an abusive mother who favored her youngest daughter. The other seven siblings all knew it, but it was especially apparent amongst the four girls. The youngest girl was my aunt Jeanette. Growing up I’d hear stories about how my aunt Jeanette wasn’t punished as often or as badly as the other kids and how my mother had to give Jeanette her car when she moved out, even though she and her twin sister had paid for it themselves.

My grandmother’s favoritism towards one sibling created family resentment and jealousy. It affected how the rest of the siblings got along. They learned to be competitive and suspicious with each other. It reminds me of the story of Joseph in the Bible. He was so heavily favored by the father that all his brothers turned on him and left him for dead. But in the end, Joseph sees them again and forgives them.

I wonder if forgiveness can stop the cycle of dysfunction. My mother was abused, and she became abusive. She and most her siblings had mental problems or substance abuse issues. I don’t know much about my maternal grandmother’s background, but I suspect she too was abused. Maybe one of her parents was also partial to one of her siblings. Is this when the die was cast, or was it even earlier?

Did my mother ever forgive her mother and father for the horrific abuse she endured as a child? I don’t know, because she seldom spoke about what happened to her. When she did mention her mother, it was often in contradictory terms. (She rarely mentioned her father at all, as her mother was the dominant figure.)

One day my mother would say—usually when she was angry—something like, “If I behaved the way you have, my mother would hit me with a cast-iron skillet or throw something at me.” Another time she’d call her mother a saint and say how much she missed her.

I got this confusing picture of my grandmother as demonic and angelic. How could she be both? Which one was true? As I aged, I began to understand. I realized my grandmother treated her children badly much of the time. Those were painful, traumatic memories that my mother did her best to suppress. But occasionally something would slip out. She’d state a fact about her childhood, and then she probably felt guilty. She was taught to be obedient and submissive to her parents. She was not allowed to speak for herself or even protect herself. Such behavior was disrespectful and subject to extreme punishment.

My sisters and I were also never allowed to say anything negative about my grandmother. She was a dark figure my mother had cast in bright light. My mother was taught that her mother’s status as the family matriarch was more important than anything else. My grandmother was allowed to be abusive but still respected, even revered. And this is also what my sisters and I were taught about our mother. The family roles were cast in stone. The mother was at the top, the father a few steps below and the children at the bottom.

When I think about my childhood, I feel sad that my sisters and I couldn’t bond over our shared experience. Instead of coming together in solidarity, we’ve splintered. My oldest sister died many years ago, depressed, lonely and imbued with pain. My middle sister and I live in different states and different worlds.

A thought about my sister runs through my brain repeatedly: if she and I could truly forgive each other, could we finally find peace? Could we release the toxic false assumptions and bad impressions we’ve made of each other over our lifetimes? Maybe if we acknowledged that these were formed from trauma, we could let them go. We learned some techniques that helped us survive then, but we don’t need them now.

Forgiving each other is the first step. Another one is discarding the family roles that keep us trapped in dysfunction. She was the big sister who took care of me. I was the little sister who needed help. When we were children, we needed those roles to stay safe. We do not need them now. They are chains to a dark past.

The third step is treating each other like friends, not sisters. We are adult women who are equals. There is no hierarchy. We can both express ourselves. We can disagree at times. We can share our mistakes and vulnerabilities with each other. I can be open to her advice, and she can be open to mine. The playing field must always be level. If it’s not, we regress.

We will always be sisters, but I wish so much we could be friends.