Some days I wonder when the shame began. Not about what I’d done, but who I am. Was it in childhood? Before my brain was developed enough to reject it? So I accepted the idea. I believed something was wrong with me, something so deeply embedded and awful I’d never be able to recover.

Some days I wonder when the shame began. Not about what I’d done, but who I am. Was it in childhood? Before my brain was developed enough to reject it? So I accepted the idea. I believed something was wrong with me, something so deeply embedded and awful I’d never be able to recover.

I first heard it from my mother, but I feel guilty saying that. My mother died last year. She was a deeply unhappy, broken woman herself. She too was full of shame. So how can I blame her? She didn’t know any better. She was abused in multiple ways by her mother, her father and probably her brothers.

I say “probably” because she never directly said she was abused. I learned of it in bits and pieces. She’d blithely comment about her mother hitting her with a skillet. She’d talk about her father being “sick” and warn my sisters and I to stay away from him. But so many other times years after her parents died, she’d say how much she loved them and how great they were. She couldn’t accept the truth. But deep down, I think she knew it.

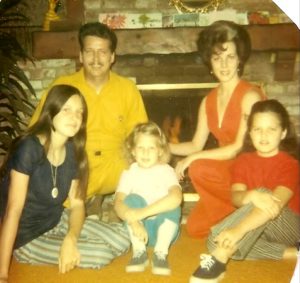

Can someone filled with shame raise three daughters who love themselves the way God intended? Can it skip a generation? Maybe she thought being a mother would help her heal her trauma. She could love and nurture her children in a way she didn’t experience.

But it didn’t happen that way. Instead, shame flowed out of my mother like blood from a wound. It spurted out in tiny, dark pools. Without even realizing it, my sisters and I stepped in it. We learned we weren’t right.

Actually, I’m not sure about my sisters. One of them is dead and the other doesn’t want to go there, so I will speak for myself. I stepped in my mother’s shame blood. It was all over me by the time I was in fifth grade. I’ve never been able to wash it off.

I’ve talked about it before in this blog. We were in the kitchen. I don’t remember what we were doing, but it must have been a bad day for my mother. Her mood probably had nothing to do with me, but that wasn’t how I felt then. Instead, I felt the full force of her anger and disgust. She said she didn’t know what happened, but “something was wrong” with me and I didn’t “turn out right.” My sisters did but I didn’t, so it had to be me. That’s what I inferred anyway.

I picture myself then, a slight 10-year-old girl with curly blonde hair and a bottom lip too full, probably wearing one of my cat t-shirts and high-waisted Ditto jeans. I see myself standing in the kitchen looking confused. One minute I was all right and the next I wasn’t, because my mother hated me.

I wish I could time-travel. As an adult I’d go back to that day decades ago. I’d pull the little girl aside and tell her not to believe anything her mother said in that moment. None of it was true. Her mother was upset. I would hug the little girl and rub her back and tell her she was fine. Everything was ok.

If I could do that, would it unwind the years of pain that followed? Sometimes I think it would, because I remember this incident as critical. When my mother said those words, they implanted on my brain.

But memories can be false. It could’ve happened before this incident or after. It could’ve been a slow death of many tiny wounds, not one big gash.

I want to remember it as one incident because it’s easier to accept. I tell myself my mother was hungover or upset about finances or angry at my dad or any number of things that put her in a bad mood that morning. I got the brunt of her anger because I was the unlucky one standing there.

The other view is harder to justify. It’s many incidents happening over years, each one stripping away at my core. It’s the times she praised my sisters and not me. The comments about how lovely Angie was or how smart Georgia was, the rest of the sentence left hanging in the air.

It’s the days I came home from school, letting myself in with a key to an empty house, a list of chores from her. It’s all those lonely hours in the house, my sisters long gone and the TV my only company. My parents would come home from work and pass through me. No questions about my day. No offer to help with my homework. No hug or “hi baby” or smile from my mother. Just a vacuum of indifference.

It’s all the Friday nights I sat eating McDonald’s off a TV tray and watching Dallas while my parents were in the kitchen drinking.

Each incident was another scratch. Some bled and some didn’t. Some were so small I probably didn’t notice them.

When you are defenseless, there are only two options: run or hide. I had nowhere to run, so I hid in my room. I’d watch TV or listen to music. Later my mother would start screaming. If I wasn’t there, my dad would get the brunt of it. But when he fell asleep, it would be my turn.

Last month I was on a video business meeting and someone mentioned Mother’s Day. I had forgotten about it. I realized why I’d felt sad all week. I also thought about Naomi Judd’s death and how she reminded me of my mother. They were both so pretty and feminine, teased hair and rhinestones and perfect make-up. Naomi was a true southern lady, like my mother.

Naomi’s suicide reminded me of how much my mother suffered, how lonely and sad she was most of her life. I believe she slowly, passively killed herself. She did it through starvation, cigarettes and pills. She cut herself off from the world. She sat alone in her tiny, dirty apartment watching TV and chain-smoking. It took a long time, but the life ebbed out of her. It was too hard to keep fighting, so she gave up.

I’m devastated thinking about my mother’s last moments alive. There was no happy ending for her. She endured so much pain for so long. I want to go back and see her again, rewind to my last visit with her in June, just four months before her death. This time, instead of leaving her there, I would say, “Mom, get your stuff, I’m taking you home.” The same words I’d said to my father six years ago. I’d help her pack and she and her little dog, Cody, would move in with my husband and me. She would never have to be alone again.

In the idyllic world in my mind, this would’ve worked. My mother would’ve finally been free of the despair that clung to her for so long. She would’ve been happy. I wish it could’ve been true. I wish I could see my mother experience joy.

I wish I could see my dad Dad again and hug him and tell him I loved him. He gave great hugs, and he loved me. I felt wrong with my mother but cherished by my Dad. I was his little “puddin.”

The last time I saw him he was lying in a hospital bed dying. Before he gave up, he tried to hold on. He let me feed him a little ice cream. He was a tiny bird, his mouth opening for a small bite, and then he shook his head, no more. He stopped eating and drinking, and I knew it was the end.

When I was 20 years old and worked at the high school, I used to pop next door to eat lunch with my father. He worked in IT—they called it Data Processing then—for the school district, in a small building next to the school. We’d sit in his office eating our lunch and reading our books. We didn’t have to say much to each other. We were book worms, cozy and content in each other’s company.

His face would light up when I arrived, just as it did that last day in the hospital. I looked at him and the years rolled back. Even when he was in the last stages of dementia, emaciated and out of it, he knew me. When I got there I said, “Hi Dad, it’s Eileen, your daughter” because I wasn’t sure he’d remember me. And he looked at me and smiled and said, “I know who you are. You’re my sweetie.”

My heart is broken into a thousand pieces. Daddy, sometimes I miss you so much I don’t want to be here anymore. I want to be with you. I want to see you smiling and eating a piece of cake I baked for you, except you wouldn’t be in a wheelchair. You’d be sitting tall at the dining room table, healthy and happy. You’d be laughing.

I miss my mother too. I wish I could’ve hugged her again, even though she didn’t like hugs. She’d air hug, but I’d hold on tight anyway and tell her I loved her. Even when she didn’t like me and I didn’t like her, I still loved her so much. My beautiful, fragile mother.

I miss my oldest sister, Angie. I wish she had died happy, but there was sorrow in her emails and phone calls. I remember her puffy face and how dull her eyes looked the last time I saw her. She had retreated into herself.

A few days later, I called her supervisor to tell her Angie had suddenly died the day after Thanksgiving. She was 51. Her supervisor said, “Angie suffered so much, for so long” and I came undone.

I think of my other sister and how far apart we are, because we came from a family steeped in dysfunction. It built a chasm between us that cannot be bridged. The Lord knows how many times we have tried and failed. It never works because we are unmatched puzzle pieces. We just don’t fit together. My sister and I are the remnants of a lost family.

I miss what it was, but mostly I miss what it could have been.

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall,

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men,

Couldn’t put Humpty together again.

by Mother Goose